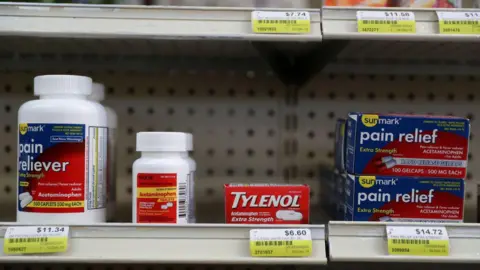

Trump makes unproven link between autism and Tylenol

US President Donald Trump said doctors would soon be advised not to prescribe the over‑the‑counter pain reliever Tylenol to pregnant women, citing a disputed link to autism.

Speaking in the Oval Office on Monday, he said taking Tylenol (acetaminophen) “is no good” and urged pregnant women to “fight like hell” to avoid it except for extreme fever — a claim medical experts immediately disputed.

Major medical groups and public health officials pushed back, saying the evidence is mixed and that paracetamol (the name for acetaminophen used outside North America) remains the recommended option for treating fever and pain in pregnancy when clinically needed.

Health officials noted that acetaminophen is commonly used by pregnant women for headaches and fever and that untreated fever can pose risks in pregnancy — so decisions about use should be made with a clinician, not headlines.

UK Health Secretary Wes Streeting said: “I trust doctors over President Trump, frankly, on this.” His comment reflected wider official scepticism about a firm Tylenol autism link and signalled that governments will rely on clinical guidance rather than political statements.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) strongly rejected the president’s announcement. The american college obstetricians said the claim was not supported by the full body of evidence and warned against oversimplifying the many causes of neurologic conditions in children.

Its president, Dr Steven Fleischman, said the suggestion of a link “is not backed by the full body of scientific evidence and dangerously simplifies the many and complex causes of neurologic challenges in children.” The college obstetricians emphasised that guidance must reflect the broader scientific literature and the totality of studies.

In a separate statement, ACOG added: “Studies that have been conducted in the past show no clear evidence that proves a direct relationship between the prudent use of acetaminophen during any trimester and fetal developmental issues.” That language echoes the distinction researchers often make between observed associations in some studies and proven causation.

The US Food and Drug Administration (food drug administration) used more measured wording in a notice to doctors. The agency said clinicians should consider limiting the use of Tylenol while also recognising that acetaminophen is the safest over‑the‑counter drug to treat fever and pain in pregnancy when needed — and that untreated fever can itself pose risks to maternal and fetal health.

“To be clear, while an association between acetaminophen and autism has been described in many studies, a causal relationship has not been established and there are contrary studies in the scientific literature,” the FDA wrote, highlighting the difference between association and causation.

Speaking alongside the president, Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr said the FDA would begin a process to consider a safety label change for the medication and launch a public health campaign to spread awareness. That proposal — if it proceeds — would involve reviews of existing data and consultation with medical experts before any formal label change.

Tylenol is a widely used brand whose active ingredient is acetaminophen (known as paracetamol outside North America). The drug is included in many clinical guidelines and is recommended by other major medical groups and governments as the first‑line option for fever and pain in pregnancy when treatment is required.

What pregnant women should do now: clinicians and public health bodies say don’t stop or start medications based on headlines — discuss acetaminophen use and alternatives with your healthcare provider if you have concerns about fever, pain, or medication in pregnancy.

Watch: Trump says taking Tylenol is “not good” for pregnant women

What the studies say: a recent review and larger population work

In August, a review led by the dean of Harvard University’s Chan School of Public Health analysed 46 published studies on the use of acetaminophen in pregnancy and neurodevelopmental outcomes. The review (link above) reported that 27 of those studies found a positive association between prenatal acetaminophen exposure and an increased risk of autism or other neurodevelopmental disorders in children; most of those studies were observational cohort or case‑control studies that relied on maternal reports or prescription records.

Those studies vary in size and method: some adjusted for maternal illness, smoking, socioeconomic factors and other confounders; others could not fully account for all potential influences. Observational studies can identify associations — patterns where two things occur together — but they cannot by themselves prove a causal relationship (that one thing directly causes the other).

For example, women with infections or high fever may be more likely both to take acetaminophen and — independently — to have inflammatory exposures that could affect fetal development. That kind of confounding can make it hard to separate the effect of the drug itself from the effect of the underlying illness.

By contrast, a 2024 large population study in Sweden looked at records for 2.4 million children born between 1995 and 2019 and did not find evidence of a relationship between prenatal acetaminophen exposure and autism diagnoses. That study’s size and registry‑based design reduced some sources of bias, but it also had limits — for example, prescription or registry data may not capture over‑the‑counter use reliably in every case.

Scientists and reviewers say the totality of evidence is mixed: many studies report an association, but observational designs, varying adjustment for confounders, potential recall bias and inconsistent exposure measurement mean the evidence does not yet meet the standard needed to conclude causation. As Monique Botha, a professor at Durham University, put it: “There is no robust evidence or convincing studies to suggest there is any causal relationship.”

What researchers say is needed now are larger, better‑controlled studies and, where possible, studies that can use biological measures of exposure (for example, biomarkers) or designs that reduce confounding — steps that will help clarify whether observed associations reflect a real effect of acetaminophen or other correlated factors.

Major medical groups say it is safe for pregnant women to take Tylenol, also known as Paracetamol

Researchers caution that the science is still at an early stage and more rigorous work is needed before drawing firm conclusions about acetaminophen and autism. Observational studies have produced mixed results, and experts say that stronger designs and more consistent exposure measurement are required to assess risk reliably.

In April, Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr pledged “a massive testing and research effort” to try to determine causes of autism within five months — a timeline researchers say is implausibly short for the complex work required to untangle genetic and environmental contributions.

President Trump described the rise in reported autism diagnoses as a “horrible crisis” and said he had “very strong feelings about” addressing it. While the political attention highlights public concern, experts stress that identifying causes is complex and requires years — not months — of careful research.

The widely held scientific view is that autism does not have a single cause: researchers point to a complex mix of genetic influences and environmental factors over time. That is why nuanced, replicable studies are needed before policy or clinical guidance changes are made.

Haley Drenon, 29, from Austin, Texas, who is pregnant for the first time, said the announcement made her nervous because she took Tylenol for headaches during her first trimester. “This announcement, if made without the proper context, would worry a lot of other people as well,” she said. “It seems a little unnecessary just because the headlines are clear that the data is not irrefutable.”

Autism diagnoses have increased since 2000; by 2020 the rate among 8‑year‑olds reported by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reached about 2.77%. Scientists attribute at least part of that rise to greater awareness and changes in diagnostic criteria, while researchers continue to investigate environmental influences.

Some commentators have noted that both Mr. Kennedy and Mr. Trump have previously promoted claims about autism that other experts have criticised — for example, debunked theories about vaccines — and warned that public messaging should not undermine families or the progress of scientific research.

Bottom line for pregnant women and mothers: public health bodies and clinicians advise that acetaminophen remains the recommended first‑line option for treating fever and pain in pregnancy when treatment is necessary; do not stop or change medication without talking to your healthcare provider.

Vaccine Panel’s Credibility Questioned as Policy Review Begins